|

| Image: Nobelprize.org |

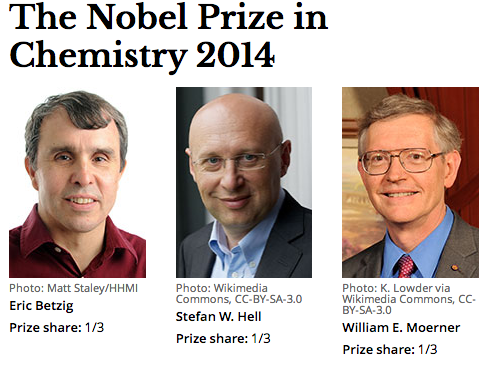

Moerner seems to have been an obvious choice on several people's lists for years while Hell and Betzig seem to have largely escaped attention.

Here's what the three prizewinners did, in a nutshell:

Two separate principles are rewarded. One enables the method stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, developed by Stefan Hell in 2000. Two laser beams are utilized; one stimulates fluorescent molecules to glow, another cancels out all fluorescence except for that in a nanometre-sized volume. Scanning over the sample, nanometre for nanometre, yields an image with a resolution better than Abbe’s stipulated limit.

Eric Betzig and William Moerner, working separately, laid the foundation for the second method, single-molecule microscopy. The method relies upon the possibility to turn the fluorescence of individual molecules on and off. Scientists image the same area multiple times, letting just a few interspersed molecules glow each time. Superimposing these images yields a dense super-image resolved at the nanolevel. In 2006 Eric Betzig utilized this method for the first time.The whole suite of single molecule techniques have huge implications for imaging, tracking and tagging molecules of all kinds, but especially so in biology. The importance of fluorescence and spectroscopy for biology have been recognized for years (as exemplified by the Nobel Prize in 2008 and 2002 for instance) but today's prize brings those techniques together and applies them to individual molecules. The prize is not only eminently well-deserved but heralds several prizes of this sort in the future as these techniques are applied to important and promising areas like neuroscience and drug discovery. In addition it is a truly interdisciplinary recognition bringing together physics, chemistry and biology. Which means that everyone should celebrate (or complain...).

There are a few interesting tidbits associated with the three scientists and their work. It seems like both Hell and Betzig were sort of in the wilderness when they made their original pioneering contributions. Hell was working in Finland, away from the mainstream research centers when he had the idea for beating the diffraction limit. And in a trend that's more common than we think, his 2000 paper on STED was rejected by Science and Nature and accepted in PNAS.

Betzig's story is especially interesting: He left academia in 1996 and worked at his father's machine tool company for several years, developing hydraulic technology which was commercially unsuccessful. But the single molecule fluorescence bug had bitten him too hard to let go, so through a series of ventures - one of which involved building a single molecule instrument with a friend in the friend's living room - he gradually returned back to academia, settling in at the Janelia Research Farm Campus in Virginia. My suspicion is that those years dabbling in technology and industry were exactly what enabled Betzig to develop his engineering acumen and apply it to building the right tools.

It's also interesting to note that both Betzig and Moerner made their original pioneering discoveries in industry - Moerner when he was working at IBM in San Jose and Betzig when he was working in his own private company. I think their stories send a clear message that interesting ideas - and especially their implementation - come quickest when good pure science collides with the kind of good engineering and practical expertise that one is exposed to in industrial settings. I think the 2014 chemistry Nobel Prize recognizes engineering as much as science and this makes it an especially important example of a tool-driven scientific revolution.

In any case, an eminently well-deserved prize with implications that are just starting to be realized and which will undoubtedly scale many new horizons in the future. Congratulations to the three prizewinners!